Erickson, The 7th Step Foundation, and His Work with Convicts

In “A Tribute to Elizabeth Moore Erickson: Colleague Extraordinaire, Wife, Mother, and Companion,” by Marilia Baker, Betty Erickson says:

“There was an organization named the Seventh Step Foundation for ex-convicts who were seriously attempting to go straight, keep out of trouble and be good citizens. I believe that Milton found out about it when he and Dr. Larson [his supervisor at the Arizona State Hospital] would make their periodic trips to the State prison, which was located in the town of Florence, south of Phoenix. There was a special division and confinement area for mentally ill lawbreakers and the two of them worked with these prisoners.

In one of those trips, Milton found out about the Seventh Step Foundation. It was originally founded in Phoenix as a place where paroled or discharged convicts could stay for a few days, get cleaned up, have good meals, and look for work, such as in a modern halfway house.”

Baker describes the 7th Step Foundation as a “program addressing, in depth, each one of the problems that led him or her to such behaviors.” Participants were encouraged to make amends for what they have done. The Foundation supported a transitional living facility in Phoenix. Betty would pack up some old clothing when Milton was going to visit the halfway house, a former mansion in the southwest area of downtown Phoenix.

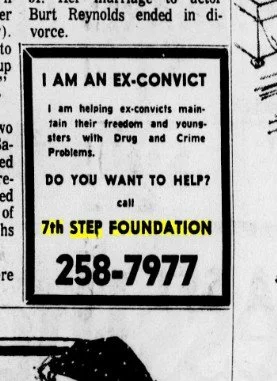

THE 7TH STEP FOUNDATION

According to the 7th Step Fellowship, Canada website:

“the 7th Step program originated in Kansas State Prison in 1963, organized by an ex-convict, Bill Sands and Reverend James Post. Bill Sands was inspired by a Warden at San Quentin by the name of Clinton Duffy. It was designed to reach the hardcore convict population, the men and women who are often the leaders within the institutions, with an end goal of reducing recidivism. Bill Sands and Reverend Post used the basics of the 12 Step Program and applied them, in principle, to getting out of prison and staying out. They re-formatted the 12 steps to make seven steps and ensured that the first letter of each step spelt FREEDOM.

The 7th Step self-help program is not a faith program, but it is based on faith. Faith in the belief that freedom can be attained and maintained if one followed and practiced the seven steps and if one would “Think Realistically”. The 7th Step Program uses a triad approach in their delivery. It is vital that ex-offenders are involved and giving back to the serving offender, whether it is in an institution or in the community. The non-offender plays a very important role in that they bring a perspective that may offer another way for the offender to think and act.”

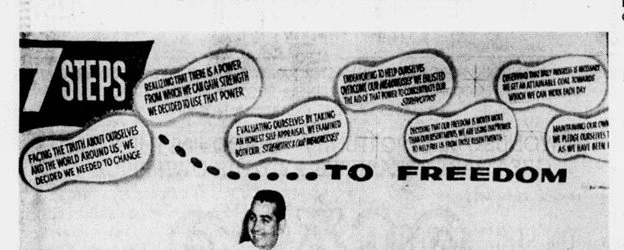

The steps that participants followed:

1. Facing the truth about ourselves and the world around us, we decided we needed to change.

2. Realizing there is a Power from which we can gain strength, we decided to use that Power.

3. Evaluating ourselves by taking an honest self-appraisal, we examined both our strengths and our weaknesses

4. Endeavoring to help ourselves overcome our weaknesses, we enlisted the aid of that Power to concentrate on our strengths.

5. Deciding our freedom is worth more than our resentments, we are using that Power to help free us from those resentments.

6. Observing that daily progress is necessary, we set an attainable goal toward which we can work each day.

7. Maintaining our own freedom, we pledge ourselves to help others as we have been helped.

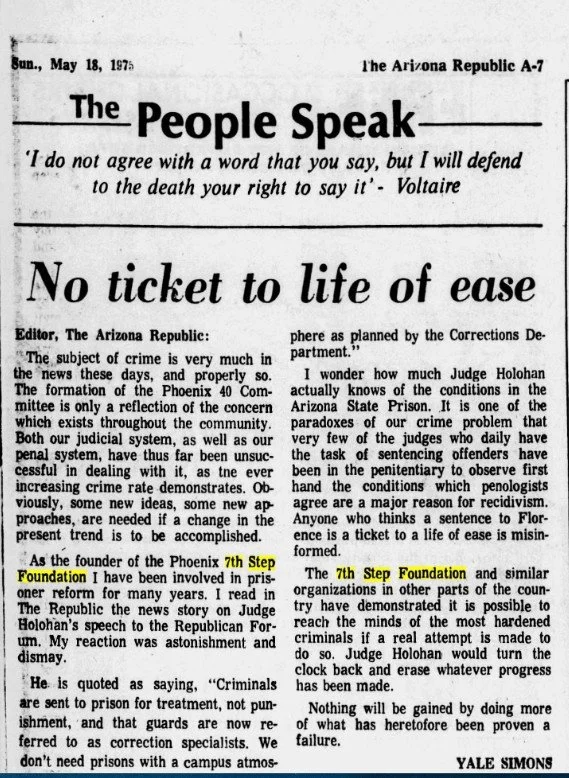

An article by Vince Taylor, a staff writer for the Central Arizona Bureau of the Arizona Republic, appeared in the March 2, 1969 edition of the paper describing the Seventh Step Foundation as “an organization to remotivate the man, to change his thinking so he can better accept the responsibilities and self-discipline he will need after years behind prison walls.”

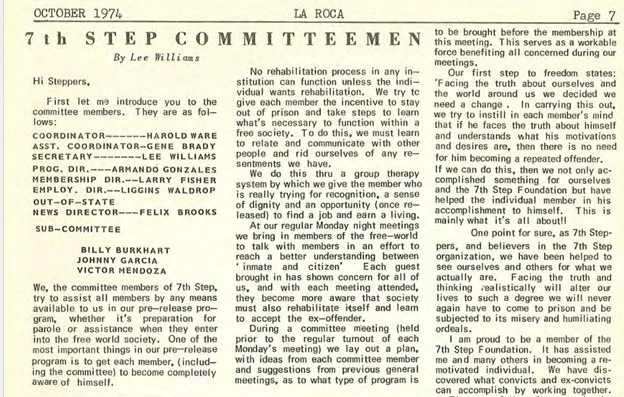

In the October 1974 edition of “La Roca: Arizona’s Penal Press,” an inmate-written newsletter of the Florence prison, Lee Williams, who had been assisted by the program, outlines the procedures of the rehabilitation process. “We must first learn to relate and communicate with other people and rid ourselves of any resentment. We do this in part through a group therapy system by which we give the member who is really trying for recognition, a sense of dignity and an opportunity [once released] to find a job and earn a living.” He further stated, “We have discovered what convicts and ex-convicts can accomplish by working together.”

You can access the October 1974 edition of the “La Roca,” through the Arizona Memory Project:

Although the Foundation seemed to flourish in the 1970’s and 1980‘s, chapters in Arizona no longer exist. However, the Foundation is still active in Oregon and is very active in Canada.

https://7thstep.ca/origin/

THE 7th STEP BACKYARD GUY

In “Phoenix: Therapeutic Patterns of Milton H. Erickson,” David Gordon and Maribeth Meyers-Anderson detail Erickson’s approach with clients. “…. a prerequisite for effective interaction with your clients is rapport, that rapport is your client knowing that you comprehend [not like] their model of the world, and that rapport can be created by mirroring your clients’ models of the world at any one [same, or all] of many possible levels, including that of ‘culture.”

Erickson recounts his experience with Paul, who was living in a 7th Step Foundation halfway house in Phoenix. Erickson reminds the reader that he worked his way through medical school by examining penal and correctional inmates in Wisconsin, “So I’ve always been interested in the subject of crime, and of course, I am a member of the 7th Step.”

Paul, the 7th Stepper, had been released from prison and was sent to see Erickson. Paul said, “I am an ex-con and Seventh Step sent me to see you to straighten me out.” Paul had spent 20 years of his 37 years in prison. Erickson listened to his story and discussed his situation with him. At the end of the session Paul said, “You know where you can shove THAT!” He visited Erickson several more times, each time Paul ended the session with “You know where you can shove THAT.” After being thrown out of his girlfriend’s home and losing his job as a bouncer, he returned to Erickson and asked, “What was that you said to me?” Erickson directs him to “stay in the backyard and think things over,” giving him a mattress and a can of pork and beans. Knowing the convict code of honor, Erickson leaves Paul with, “if you want me to confiscate your boots you’ll have to beg me,” knowing that saying that puts Paul on his honor not to run away. He stays in the backyard and then searches for a job. He rehabilitates the junk car sitting in his girlfriend’s driveway and ends up going to Alcoholics Anonymous with the girlfriend. At the time of the writing, Paul was sober for 4 years.

Erickson ends the chapter:

“You have to hit patients in the right way in order to get them to accept therapy. They want SOME change. They don’t know how to MAKE the change. All you do is create a situation that’s favorable and say ‘giddy-up’ and keep their nose on the road.”

Commentary

Paul said he was sent to Erickson for Erickson to ‘straighten him out’ and initially was dismissive of Erickson. After experiencing being tossed out of his girlfriend’s apartment and losing his job, he started taking responsibility for himself and accepting therapy and making constructive changes. And Erickson facilitated the change process through his understanding of prison culture and Paul’s defiance. He left it to Paul to “think about it” and decide on the direction he wanted to take.

joyce bavlinka, m.ed., liac