Erickson Paper on Pain Control

Milton Erickson’s paper, “An Introduction to the Study and Application of Hypnosis for Pain Control,” was first published in French in 1965 in Cahiers D’Anesthesiologie. It was later published in English in April 1967 in College of General Practice of Canada Journal.

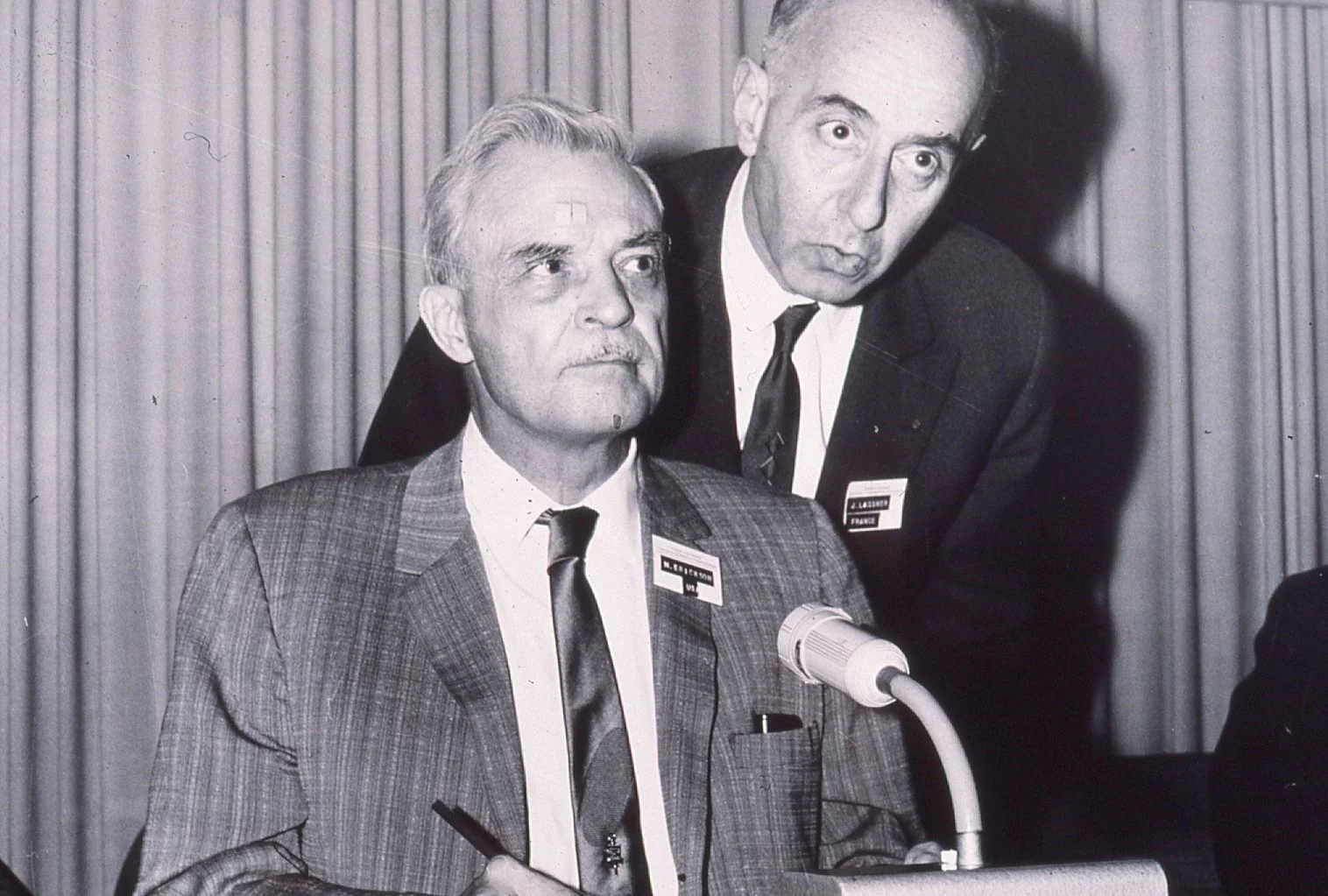

Milton Erickson (L) and Jean Lassner (R) at the 1965 International Congress for Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine in Paris, France

Erickson presented the paper during the 1965 International Congress for Hypnosis and Psychosomatic Medicine, held in Paris, France from April 28 to 30. It was a landmark event organized under the patronage of the World Federation for Mental Health and hosted by French physician, Jean Lassner. The congress brought together international experts to discuss the role of hypnosis in psychosomatic medicine, focusing on its applications in psychotherapy, neurology, and behavioral science. The proceedings, later published by Springer, documented clinical research and theoretical debates on hypnosis as an altered state of consciousness versus a cognitive-behavioral phenomenon. The event played a crucial role in the professionalization of hypnosis, contributing to the formation of international networks such as the International Society of Hypnosis (ISH).

The following is the introduction for the paper.

INTRODUCTION

Hypnosis is essentially a communication of ideas and understandings to a patient in such a fashion that he will be most receptive to the presented ideas and thereby motivated to explore his own body potentials for the control of his psychological and physiological responses and behavior.

The average person is unaware of the extent of his capacities of accomplishment which have been learned through the experiential conditionings of this body behavior through his life experiences. To the average person in his thinking, pain is an immediate subjective experience, all-encompassing of his attention, distressing, and to the best of his belief and understanding, an experience uncontrollable by the person himself.

Yet as a result of experiential events of his past life, there has been built up within his body, although all unrecognized, certain psychological, physiological, and neurological learnings, associations, and conditionings that render it possible for pain to be controlled and even abolished. One need only to think of extremely crucial situations of tension and anxiety to realize that the severest pain vanishes when the focusing of the sufferer’s awareness is compelled by other stimuli of a more immediate, intense, or life-threatening nature.

From common experience, one can think of a mother suffering extremely severe pain and all-absorbed in her pain experience. Yet she forgets it without effort or intention when she sees her infant dangerously threatened or seriously hurt. One can think of men in combat seriously wounded, but who do not discover their injury until later. There are numerous such comparable examples common in medical experience.

Such abolition of pain occurs in daily life in situations where pain is taken out of awareness by more compelling stimuli of another character. The simplest example of all is the toothache forgotten on the way to the dentist’s office, or the headache lost in the suspenseful drama portrayed at the cinema. By such experiences as these in the course of a lifetime, be they major or minor, the body learns a wealth of unconscious psychological, emotional, neurological and physiological associations and conditionings. These unconscious learnings repeatedly reinforced by additional life experiences constitute the source of the potentials that can be employed through hypnosis to control pain intentionally without resorting to drugs.

CONSIDERATIONS CONCERNING PAIN

While pain is a subjective experience with certain objective manifestations and accompaniments, it is not necessarily a conscious experience only. It occurs without conscious awareness in states of sleep, in narcosis, and even under certain types of chemo-anesthesia as evidenced by objective accompaniments and as has been demonstrated by experimental hypnotic exploration of past experiences by patients. But because pain is primarily a conscious subjective experience, with all manner of unpleasant, threatening, even vitally dangerous emotional and psychological significances and meanings, an approach to the problem it represents can be made frequently by hypnosis sometimes easily, sometimes with great difficulty, and the extent of pain is not necessarily a factor.

In order to make use of hypnosis to deal with pain, one needs to look upon pain in a most analytical fashion. It has certain temporal, emotional, psychological, and somatic significances. It is a compelling motivating force in life’s experience. It is a basic reason for seeking medical aid.

Pain is a complex, a construct, composed of past remembered pain, of present pain experience, and of anticipated pain of the future. Thus, immediate pain is augmented by past pain and is enhanced by the future possibilities of pain. The immediate stimuli are only a central third of the entire experience. Nothing so much intensifies pain as the fear that it will be present on the morrow [tomorrow]. It is likewise increased by the realization that the same or similar pain was experienced in the past, and this and the immediate pain render the future even more threatening. Conversely the realization that the present pain is a single event which will come definitely to a pleasant ending serves greatly to diminish pain. Because pain is a complex, a construct, it is more readily vulnerable to hypnosis as a modality of dealing successfully with it than it would be were it simply an experience of the present.

Pain as an experience is also rendered more susceptible to hypnosis because it varies in its nature and intensity and hence, through life experiences, it acquires secondary meanings resulting in varying interpretations of the pain. Thus, the patient may regard his pain in temporal terms, such as transient, recurrent, persistent, acute, or chronic. These special qualities each offer varying possibilities of hypnotic approaches.

Pain also has certain emotional attributes. It may be irritating, all-compelling of attention, troublesome, incapacitating, threatening, intractable, or vitally dangerous. Each of these aspects leads to certain psychological frames of mind with varying ideas and associations, each offering special opportunities for hypnotic intervention.

One must also bear in mind certain other very special considerations. Long continued pain in an area of the body may result in a habit of interpreting all sensations in that area as pain in themselves. The original pain may be long since gone, but the recurrence of that pain experience has been conducive to a habit formation that may in turn lead to actual somatic disorders painful in character.

Of a somewhat similar character are iatrogenic disorders and disease arising from a physician’s poorly concealed concern and distress over his patient. Iatrogenic illness has a most tremendous significance because in emphasizing that if there can be psychosomatic disease of iatrogenic origin, it should not be overlooked that conversely, iatrogenic health is fully as possible and of far greater importance to the patient. And since iatrogenic pain can be produced by fear, tension, and anxiety, so can freedom from it be produced by the iatrogenic health that may be suggested hypnotically.

Pain as a protective somatic mechanism should not be disregarded as such. It motivates the patient to protect the painful areas, to avoid noxious stimuli and to seek aid. But because of the subjective character of the pain, there develops psychological and emotional reactions to the pain experience that eventually result in psychosomatic disturbances from unduly prolonged protective mechanisms. These psychological and emotional reactions are amenable to modification and treatment through hypnosis in such psychosomatic disturbances.

To understand pain further, one must think of it as a neuro-psycho-physiological complex characterized by various understandings of tremendous significance to the sufferer. One need only to ask the patient to describe his pain to hear it variously described as dull, heavy, dragging, sharp, cutting, twisting, burning, nagging, stabbing, lancinating, biting, cold, hard, grinding, throbbing, gnawing, and a wealth of other such adjectival terms.

These various descriptive interpretations of the pain experience are of marked importance in the hypnotic approach to the patient. The patient who interprets his subjective pain experience in terms of various qualities of differing sensations is thereby offering a multitude of opportunities to the hypnotherapist to deal with the pain. To consider a total approach is possible, but more feasible is the utilization of hypnosis in relaxation first to minor aspects of the total pain complex and then to increasingly more severely distressing qualities. Thus, minor successes will lay a foundation for major successes in relations to the more distressing attributes of the neuro-psycho-physiological complex of pain and understanding and cooperation of the patient for hypnotic intervention are more readily elicited. Additionally, any hypnotic alterations of any single interpretive quality of the pain sensation serves to effect an alteration of the total pain complex.

Another important consideration in the matter of understanding the pain complex is the recognition of the experiential significances of various attributes in such matters as remembered pain, past pain, immediate pain, enduring pain, transient pain, recurrent pain, enduring persistent pain, intractable pain, unbearable pain, threatening pain, etc. In applying these considerations to various subjective elements of the pain complex, hypnotic intervention is greatly accelerated. Such analysis offers greater opportunity for hypnotic intervention at a more understanding and comprehensive level. It becomes more easy to communicate ideas and understandings through hypnosis and to elicit the receptiveness and responsiveness so vital in securing good response to hypnotic intervention. It is also important to recognize adequately the unrecognized force of the human emotional need to demand the immediate abolition of pain, both by the patient himself and by those in attendance on him. In hypnotic intervention there is a need to be aware of this, and not to allow it to dominate a scientific hypnotic approach to the problem of pain.

HYPNOTIC PROCEDURES IN PAIN CONTROL

The hypnotic procedures in handling pain are numerous in character. The first of these, most commonly practiced but frequently not genuinely applicable, is the use of DIRECT HYPNOTIC SUGGESTION FOR TOTAL ABOLITION OF PAIN. With a certain limited number of patients, this is a most effective procedure. But too often it fails, serving to discourage the patient and to prevent further use of hypnosis in his treatment. Also, its effects while they may be good are sometimes too limited in duration and this may limit the effectiveness of the PERMISSIVE INDIRECT HYPNOTIC ABOLITION OF PAIN. This is often much more effective, and although essentially similar in character to direct suggestion, it is worded and offered in a fashion much more conducive of patient receptiveness and responsiveness.

A third procedure for hypnotic control of pain is the utilization of AMNESIA. In everyday life we see the forgetting of pain whenever more threatening or absorbing experiences secure the attention of the sufferer. An example is the instance already cited of the mother enduring extreme pain, seeing her infant seriously injured, forgetting her own pain in the anxious fears about her child. Then of quite opposite psychological character is the forgetting of painful arthritis, headache or toothache while watching an all-absorbing suspenseful drama on a cinema screen.

But amnesia in relationship to pain can be applied hypnotically in a great variety of ways. Thus, one may employ partial, selective or complete amnesias in relationship to selected subjective qualities and attributes of sensation in the pain complex as described by the patient as well as to the total pain experience.

A fourth hypnotic procedure is the employment of HYPNOTIC ANALGESIA, which may be partial, complete, or selective. Thus, one may add to the patient’s pain experience a certain feeling of numbness without a loss of tactile or pressure sensations. The entire pain experience then becomes modified and different and gives the patient a sense of relief and satisfaction, even if the analgesia is not complete. The sensory modifications introduced into the patient’s subjective experience by such sensations such as numbness, and increase in warmth and heaviness, relaxation, etc. serve to intensify the hypnotic analgesia to an increasingly more complete degree.

HYPNOTIC AMNESIA is a fifth method in treating pain. This is often difficult and may sometimes be accomplished directly, but is more often best accomplished indirectly by the building of psychological and emotional situations that are contradictory to the experience of the pain, and which serves to establish an anesthetic reaction to be continued by posthypnotic suggestion.

A sixth hypnotic procedure useful in handling pain concerns the matter of suggestion to effect the HYPNOTIC REPLACEMENT OR SUBSTITUTION OF SENSATIONS. For example, one cancer patient suffering intolerable intractable pain responded most remarkably to the suggestion of an intolerable incredibly annoying itch on the sole of her foot. Her body weakness occasioned by the carcinomatosis and hence inability to scratch the itch rendered this psychogenic pruritus all-absorbing of her attention. Then hypnotically, there was systematically induced feelings of warmth, of coolness, of heaviness, and of numbness for various parts of her body where she suffered pain. And the final measure was the suggestion of an endurable but highly unpleasant and annoying minor burning-itching sensation at the site of her mastectomy. This procedure of replacement substitution sufficed for the patient’s last six months of her life. The itch of the sole of her foot gradually disappeared but the annoying burning-itching at the site of her mastectomy persisted.

HYPNOTIC DISPLACEMENT OF PAIN is a seventh procedure. This is the employment of a suggested displacement of the pain from one area of the body to another. This can be well illustrated by the instance of a man dying from prostatic metastatic carcinomatosis and suffering with intractable pain in both the states of drug narcosis and deep hypnosis, particularly abdominal pain. He was medically trained, understood the concept of referred and displaced pain and in the hypnotic trance readily accepted the idea that, while the intractable pain in his abdomen was the pain that would actually destroy him, he could readily understand that equal pain in his left hand could be entirely endurable, since in that location it would not have its threatening significances. He accepted the idea of referral of his abdominal pain to his left hand and thus remained free of body pain and became accustomed to the severe pain in his left hand which he protected carefully. This hand pain did not interfere in any way with his full contact with his family during the remaining three months of his life. It was disclosed that the displaced pain to the left hand often gradually diminished, but the pain would be greatly increased upon incautious inquiry.

This possibility of displacement of pain also permits a displacement of various attributes of the pain that cannot otherwise be controlled. By this measure these otherwise uncontrollable attributes become greatly diminished. Thus, the total complex of pain becomes greatly modified and made more amenable to hypnotic intervention.

HYPNOTIC DISSOCIATION can be employed for pain control, and the usual most effective methods are those of TIME AND BODY DISORIENTATION. The patient with pain intractable to both drugs and hypnosis can be hypnotically reoriented in time to the earlier stages of his illness when the pain was of minor consideration. And the disorientation of that time characteristic of the pain can be allowed to remain as a posthypnotic continuation through the waking state. Thus, the patient still has his intractable pain, but it has been rendered into a minor consideration as it had been in its original stages.

One may sometimes successfully reorient the patient with intractable pain to a previous time predating his illness and, by posthypnotic suggestion, effect a restoring of the normal sensations existing before his illness. However, although intractable pain often prevents this as a total result, pleasant feelings predating his illness may be projected into the present to nullify some of the subjective qualities of his pain complex. Sometimes this effects a major reduction in pain.

In the matter of BODY DISORIENTATION, the patient is hypnotically dissociated and induced to the experience himself as apart from his body. Thus, one woman with the onset of unendurable pain, in response to posthypnotic suggestions, would develop a trance state and experience herself as being in another room while her suffering body remained in her sickbed. This patient explained to the author when he made a bedside call, “Just before you arrived, I developed another horrible attack of pain. So I went into trance, got into my wheelchair, came out into the living room to watch a television program, and I left my suffering body in the bedroom.” And she pleasantly and happily told [me] about the fantasied television program she was watching. Another such patient remarked to her surgeon, “You know very well, doctor, that I always faint when you start changing my dressings because I can’t endure the pain, so if you don’t mind, I will go into a hypnotic trance and take my head and feet and go into the solarium and leave my body here for you to work on.” The patient further explained, “I took a position in the solarium where I could see him [the surgeon] bending over my body but I could not see what he was doing. Then I looked out the window and when I looked back, he was gone, so I took my head and feet and went back and joined my body and felt very comfortable.” This particular patient had been trained in hypnosis by the author many years previously, had subsequently learned autohypnosis, and thereafter induced her own autohypnotic trance by the phrase, “You know very well, doctor…” This was a phrase that she could employ verbally or mentally at any time and immediately go into trance for the psychological-emotional experience of being elsewhere, away from her painful body, there to enjoy herself and remain until it was safe to return to her body. In this trance state, which she protected very well from the awareness of others, she would visit with her relatives, but experience them as with her in this new setting while not betraying that personal orientation.

A ninth hypnotic procedure in controlling body pain, which is very similar to replacement or substitution of sensations, is HYPNOTIC REINTERPRETATION OF PAIN EXPERIENCE. By this is meant reinterpreting for the patient in hypnosis of a dragging, gnawing, heavy pain as a feeling of weakness, of profound inertia, and then as relaxation with the warmth and comfort that accompanies muscular relaxation. Stabbing, lancinating and biting pains may sometimes be reinterpreted as a sudden startled reaction, disturbing in character but momentary and not painful. Throbbing, nagging, grinding pain has been successfully reinterpreted as the unpleasant but not distressing experience of the rolling sensations of a boat during a storm, or even as the throbbing that one so often experiences from a minor cut on the fingertip and of no greater distressing character. Full awareness of how the patient experiences his pain sensation is requisite for an adequate hypnotic reinterpretation of his pain sensation.

HYPNOTIC TIME DISTORTION, first described by Cooper and then later developed by Cooper and Erickson (Cooper, L. and Erickson, M.H., Time Distortion in Hypnosis. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1959) is often a most useful hypnotic measure in pain control. An excellent example is that of the patient with intractable attacks of lancinating pain which occurs approximately every twenty to thirty minutes, night and day, and which lasted from five to ten minutes. Between the attacks the patient’s frame of mind was essentially one of fearful dread of the next attack. By employing hypnosis and teaching him time distortion, it was possible to employ, as is usually the case in every patient, a combination of several of the measures being described here. In the trance state, the patient was taught to develop an amnesia for all past attacks of pain. He was then taught to have an awareness of possible future attacks of pain. He was then taught time distortion so that he could experience the five to ten minute pain episodes in ten to twenty seconds. He was given posthypnotic suggestions to the effect that each attack would come as a complete surprise to him, that when the attack occurred he would develop a trance state of ten to twenty seconds of duration, experience all of the pain attack and then come out of the trance with no awareness that he had been in a trance or that he had experienced pain. Thus, the patient, in talking to his family, would suddenly and obviously go into the trance state with a scream of pain, and perhaps ten seconds later come out of the trance state, look confused for a moment, and then continue his interrupted sentence.

An eleventh hypnotic procedure is that of offering HYPNOTIC SUGGESTIONS EFFECTING A DIMINUTION OF PAIN, but not a removal, when it has become apparent that the patient is going to be fully responsive. This diminution is usually brought about best by suggesting to the hypnotized patient that his pain is going to diminish imperceptibly hour after hour without his awareness that it is diminished until perhaps several days have passed. He will then become aware of a definite diminution either of all pain or of specific pain qualities. By suggesting that the diminution occur imperceptibly, the patient cannot refuse the suggestion. His state of emotional hopefulness, despite his emotional despair, leads him to anticipate that in a few days there may be some diminution; particularly that there may be even a marked diminution of certain of the special attributes of his pain experience. This, in itself, serves as an autosuggestion to the patient. In certain instances, however, he is told that the diminution will be to a very minor degree. One can emphasize this by utilizing the ploy that a 1 percent diminution of his pain would not be noticeable, nor would a 2 percent, nor a 3 percent, nor a 4 percent, nor a 5 percent diminution, but that such an amount would nevertheless be a diminution. One can continue the ploy by stating that a 5 percent diminution the first day and an additional 2 percent the next day still would not be perceptible. And if on the third day there occurred a 3 percent diminution, this too would be imperceptible. But it would total a 10 percent diminution of the original pain. This same series of suggestions can be continued to a reduction of pain to 80 percent of its original intensity, then to 70 percent, 50 percent, 40 percent, and sometimes even down to 10 percent. In this way the patient may be led progressively into an ever-greater control of his pain,

However, in all hypnotic procedures for the control of pain one bears in mind the greater feasibility and acceptance to the patient of indirect as compared with direct hypnotic suggestions and the need to approach the problem by indirect and permissive measures and by the employment of a combination of various methodological procedures described above.

SUMMARY

Pain is a subjective experience, and it is perhaps the most significant factor in causing people to seek medical aid. Treatment of pain as usually viewed by both physician and patient is primarily a matter of elimination or abolition of the sensation. Yet pain in itself may be serving certain useful purposes to the individual. It constitutes a warning, a persistent warning of the need for help. It brings about physical restrictions of activity, thus frequently benefiting the sufferer. It instigates physiological changes of a healing character in the body. Hence, pain is not just an undesirable sensation to be abolished, but rather an experience to be so handled that the sufferer benefits. This may be done in a variety of ways, but there is a tendency to overlook the wealth of psycho-neuro-physiological significances pain has for patient. Pain is a complex, a construct composed of great diversity of subjective interpretative and experiential values for the patient. Pain, during life’s experience, serves to establish body learnings, associations, and conditionings that constitute a source of body potentials permitting the use of hypnosis for the study and control of pain. Hypnotic procedures, singly or in combination, for major or minor effects in the control of pain described for their application are:

Direct Hypnotic Suggestion for Total Abolition of Pain

Permissive Indirect Hypnotic Abolition of Pain

Amnesia

Hypnotic Analgesia

Hypnotic Replacement or Substitution of Sensations

Hypnotic Displacement of Pain

Hypnotic Dissociation.

Reinterpretation of Pain Experience

Hypnotic Suggestions Effecting a Diminution of Pain